Here's the full text:

Shine on, Harvest moon

You always knew it was going to be something interesting when we were working with Harvest. Out of the mainstream, sometimes wacky, and you would be working until the early hours – not for the faint-hearted.

Peter Mew, Abbey Road engineer

It’s faintly ridiculous, the sense of nostalgia that the sight of certain record labels can evoke in music fans of a certain age. After all, who bought an album for the label it was released on? However, a handful of those logos stood out, representing companies that have now garnered cult status and are considered to represent the importance of artistry over ribald commerciality. And in the front rank was Roger Dean’s ‘harvest moon over a valley’ design set on a light green background that signified a Harvest Records release.

As rock music became the dominant artform of the late 1960s, and the underground became a recognisable ‘scene’, major British record companies sat up and took notice. Whilst Island had been increasingly thriving in the UK since 1962 – founder Chris Blackwell signed underground groups such as Traffic, King Crimson and Fairport Convention – other longer-established labels were keen to get involved with the new wave of creativity. In 1969, Philips Records introduced its new Vertigo label – with its Op Art black-and-white spiral – specifically launched to specialise in the burgeoning progressive rock movement. And in the same year, EMI did the same, starting their underground subsidiary, Harvest.

This was the era of the record label as brand, and of course America led the way. By mid-1969, underground papers in Britain such as International Times were featuring half- and full-page advertisements from US companies, including Elektra and CBS, the latter notable for their timely adoption of the radical fervour of the era, assuring the prospective record buyer that ‘the revolutionaries are on CBS’.

It’s faintly ridiculous, the sense of nostalgia that the sight of certain record labels can evoke in music fans of a certain age. After all, who bought an album for the label it was released on? However, a handful of those logos stood out, representing companies that have now garnered cult status and are considered to represent the importance of artistry over ribald commerciality. And in the front rank was Roger Dean’s ‘harvest moon over a valley’ design set on a light green background that signified a Harvest Records release.

As rock music became the dominant artform of the late 1960s, and the underground became a recognisable ‘scene’, major British record companies sat up and took notice. Whilst Island had been increasingly thriving in the UK since 1962 – founder Chris Blackwell signed underground groups such as Traffic, King Crimson and Fairport Convention – other longer-established labels were keen to get involved with the new wave of creativity. In 1969, Philips Records introduced its new Vertigo label – with its Op Art black-and-white spiral – specifically launched to specialise in the burgeoning progressive rock movement. And in the same year, EMI did the same, starting their underground subsidiary, Harvest.

This was the era of the record label as brand, and of course America led the way. By mid-1969, underground papers in Britain such as International Times were featuring half- and full-page advertisements from US companies, including Elektra and CBS, the latter notable for their timely adoption of the radical fervour of the era, assuring the prospective record buyer that ‘the revolutionaries are on CBS’.

The new British labels were less declamatory – Decca’s subsidiary Deram never resorted to invoking left-wing radicalism in their sales pitch – but they did reflect the plurality of music stemming from the counterculture. This was the dawning of ‘progressive’ rock (then more a statement of intent than the recognisable genre it became), and EMI’s Harvest label had Pink Floyd, the darlings of the UK underground and prog pioneers.

Harvest was set up by former Manchester University economics graduate Malcolm Jones, who joined EMI in 1967 as a trainee manager. Jones managed to persuade the powers-that-be to launch Harvest in June 1969, bringing together a number of dispirate acts that were signed to older, established labels. New recruits Barclay James Harvest (who apparently gave the new company its name) and Deep Purple were originally on the roster of Parlophone, and Pink Floyd were recording for Colombia. In the spirit of the times, Jones deviated from the more established companies’ A&R policy, employing Andrew King and Pete Jenner of Blackhill Enterprises, organisers of the huge free concerts seen in Hyde Park. King and Jenner were also the original managers of Pink Floyd, and came with the prerequisite underground cachet. Jenner certainly thought so himself, telling the NME in 1989 that ‘I thought I had golden ears, I thought everything I heard and quite liked would be a hit.’

There is no need to add anymore to the story of the Floyd, of course, except to say there was plenty of talent on Harvest that made for far more interesting listening than the studio LP of Ummagumma. We can also pass over the debut album by Deep Purple (The Book of Taliesyn), and disregard the label’s two future rock monoliths for the more interesting stuff.

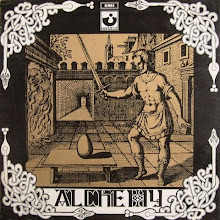

And what an eclectic, interesting bunch of records was released in Harvest’s 1969–73 period. In the second half of 1969 alone, the label engaged with traditional English folk (Shirley and Dolly Collins’ Anthems in Eden), free form folk/jazz/classical esoterica (the Third Ear Band’s Alchemy), original and diverse singer-songwriters (Michael Chapman’s Rainmaker and Kevin Ayres’ Joy of a Toy), and Wasa-Wasa, the debut by psych-festival freak favourites the Edgar Broughton Band.

The creativity of the music was matched by the attention paid to the artwork. The renowned SHVL* series (the catalogue name and number seen on the vinyl’s distinctive label) produced glossy artwork from the likes of designers Hipgnosis in a gatefold sleeve – perfect for skinning-up whilst enjoying the sounds of Flat Baroque and Berserk (1970) by Roy Harper.

And it was 1970 when the label had its golden age. No less than twenty-six records were released that year, including the label’s double-set sampler, Picnic – A Breath of Fresh Air. EMI also ensured that the label was distinct from the mother-company, as future label head Mark Rye described in 2014: ‘The Harvest office was just this dark corner, as far away from everyone else as you could get. It had cushions on the floor rather than desks and chairs…’

1971 would see the last album by the Move (Message from the Country) before they mutated into the Electric Light Orchestra, their debut album released on the label towards the end of the year. Roy Wood went on to form Wizzard, who would have Harvest’s strongest single success with ‘I Wish it Could be Christmas Everyday’, reaching #4 in the UK singles chart in December 1973. Artistically, however, the label had peaked by this point.

Whilst The Dark Side of the Moon enjoyed huge sales, many of Harvest’s original signings had moved to other labels, or fallen by the wayside as the underground ebbed away. Aside from the Floyd’s subsequent releases, the mid-1970s were an uncertain time for the label; when EMI signed the Sex Pistols in 1976, the band declined to be on Harvest, considering its artists to be ‘hippie shit’. The label would continue through into the 1980s, but by the middle of the decade Harvest lay dormant. It was revived in 2006 by EMI A&R man Nigel Reeve and has relocated to the US as part of Capitol.

That is of course, a long way from the label’s origins. The formation of Harvest reminds one of a brief time when the majors relinquished control to the hip, therefore creating a space for freedom and progression. Although it was bound to pass, the four-year period from 1969-1973 saw Harvest release music that was original and progressive in the best sense of the term. How often does one genuinely see that these days?

* SHVL stood for ‘Stereo Harvest Very Luxurious’.

Notable Harvest Releases 1969–1973

1969

Shirley and Dolly Collins – Anthems in Eden

Michael Chapman – Rainmaker

Third Ear Band – Alchemy

Kevin Ayers – Joy of a Toy

1970

Syd Barrett – The Madcap Laughs

Roy Harper – Flat Baroque and Berserk

Shirley and Dolly Collins – Love, Death and the Lady

Edgar Broughton Band – Sing Brother Sing

Pete Brown & Piblokto! – Things May Come and Things May Go but the Art School Dance Goes on Forever

Barclay James Harvest – Barclay James Harvest

Shirley and Dolly Collins – Love, Death and the Lady

Third Ear Band – Third Ear Band

The Pretty Things – Parachute

Syd Barrett – Barrett

Various Artists – Picnic: A Breath of Fresh Air (sampler)

Michael Chapman – Fully Qualified Survivor

1971

The Move – Message From the Country

Pink Floyd – Meddle

Kevin Ayers – Whatevershebringswesing

1973

Roy Wood – Boulders

Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon

Electric Light Orchestra – ELO 2

Kevin Ayers – Bananamour

Roy Harper – Lifemask

no©2019 Luca Chino Ferrari (unless you intend to make a profit. In which case, ask first)